Hundi: Why is it so popular now?

Hundi has been in place in this region since ancient times and it never ever came to a halt. That informal system of fund transfer in recent times has increased significantly. It is because money laundering has increased that hundi is in higher demand. And as the price of the dollar is higher in the kerb market, it is not just overseas remittance that is coming in by means of hundi. Actually, it is the increase in money laundering that has sparked off the increase in hundi. It is members of the wealthy business community who basically siphon out funds in the guise of international trade. And those who earn money through bribes, corruption, tax evasion, smuggling and other underhand means, choose hundi to launder their money.

History of hundi

There was a time when hundi was legitimate and safe. Now it is neither safe nor legitimate. In the 18th century, trading was carried out along the Silk Route stretching from China to the Mediterranean. It was not safe to carry cash or valuables back then because of robbers. And that is when hundi developed.

Hundi and hawala are one and the same. The word ‘hawala’ has Arabic roots and ‘hundi’ Sanskrit roots. ‘Hawala’ is used in India and ‘hundi’ in Bangladesh and Pakistan. In the Middle East and Africa they use the word ‘hawala’ too. This means transaction or transfer or anything.

Historian Sirajul Islam wrote in Banglapaedia that hundi is a form of informal monetary instruments developed under the economic expansion and consequent monetisation processes of the Mughal economy. In the seventeenth century, the land revenue from Bengal was dispatched to Delhi by qafilas or train of bullock-carts. Such a system was both expensive and unsafe. Furthermore, the local economy suffered from the shortage of coins for a long time since the royal remittance. The problem was solved by the hundi system. Among those traders most famous was the house of Jagat Seth Mahtab Chand during the later Mughal period. The rise of modern banking system in Bengal from the late 18th century led to the decline of hundi system from the early nineteenth century. But because hundi was once a safe system of money transfer, it now poses as a big problem for the economy.

Sujan Rai Bhandari wrote the history of the Mughal Empire in Persian. The writing was completed in 1695-96 during Aurangzeb’s rule. The book, Khulasat–ut–Tawarikh, has detailed description of the banking system and hundi of those times.

Sujan Rai Bhandari wrote that, in business transactions, the honesty of the people of this country was such that they would deposit millions of taka in cash to an unknown ‘sarraf’ of banker (money-changer) without any witness, knowing they would soon get that money back in all honesty. If there was fear of robbery in carrying money over a long distance during travel, the banker would write a note, without any seal or envelope even, and that is locally known as hundi. The ‘sarraf’ would have ‘agents’ all over the country who would carry out the transactions and pay the hundi amount without any fuss. And if the person wanted his payment in a place where there was no agent, he could just sell that chit of paper and get the full amount. That chit was nothing but two lines in handwriting, but could be sold for the same amount of money. They buyer would get a slight commission. That hundi could then be cashed in the specified place. Interestingly, if a trader apprehended robbery during transportation of his goods, he could give the responsibility of the valuable goods or commercial cargo to that ‘sarraf’ or banker. These honest ‘sarrafs’ would charge an ‘uzrat’ or percentage on the value of the goods and this was a sort of insurance. (Source: Indian Economy Under Early British Rule 1757-1857, Irfan Habib)

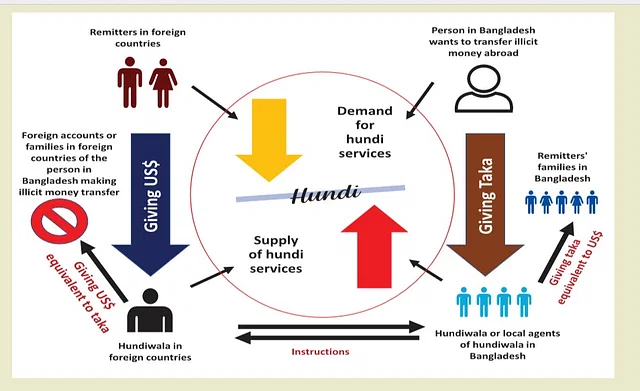

Why hundi is in high demand

Why is hundi so popular? Is hundi increasing because when sending money home, expatriates want to get a higher rate for the dollar than provided by banking channels, or because it has become necessary to buy and sell dollars informally within the country? The bottom line is demand. Hundi has increased because demand has increased. The dollar rate is not important to those who will carry out money transacts in various ways. The hundi-wallas simply fix the dollar rate according to demand.

The American citizen Forrest Cookson came to Bangladesh in the nineties as a consultant for the financial sector reforms programme. He also became the president of the American Chamber of Commerce. He had done some writing about hundi in 2018. There he had broadly identified five demands for foreign currency in Bangladesh. These were:

1. Under invoicing of imports: USD 10-15 billion per annum and growing.

2. Indian and Sri Lankan nationals working in Bangladesh (largely in the RMG industry) sending funds home: USD 3-4 million per annum.

3. Capital flight by Bangladeshi nationals: USD 1-2 billion per annum.

4. Payment of bills for education and medical care largely in India: USD 1.0 billion per annum

5. Coverage of the trade deficit of the informal trade between India and Bangladesh: USD 1-3 billion per annum.

These demands total USD 16-25 billion per annum, which are transacted through illegal channels. That is why hundi has increased so much.

Largest channel for money laundering

According to the Washington-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) report, USD 49.65 billion was laundered out of Bangladesh from 2009 to 2014. This money transfer is basically done under the cover of import and export transactions.

Money laundering in the guise of business is the work of the wealthy and influential. Over-invoicing and under-invoicing is the main tool of trading-based money laundering. Over-invoicing entails falsification of the trade documentation, drawing up an invoice with the product price mentioned much higher than the market price, and exporting the product. So the seller gets a higher sum from the buyer and this doesn’t come into the country. That means the importer can illegally launder the money through the exporter in the outside country. Under-invoicing is possible in imports if there is a middle persons involved to contact the buyer and help in the laundering. The main objective is to transfer wealth to a different country.

Under-invoicing means displaying a price lower than actual. This is basically done to evade taxation. If a lower price is shown, the actually amount is sent through hundi to the importer. On 1 December, the governor of Bangladesh Bank gave an example of how an LC was opened to import a USD 100,000 Mercedes Benz with the price shown as just USD 20,000. The remaining amount is sent through hundi.

So is lowering taxes the solution? In the interests of industrialisation, minimum duty is imposed on the import of capital machinery. As very little duty is leveraged from here, there is not much scrutiny during import. Basically this is the most popular method of money laundering for the wealthy.

In 2018 Forrest Cookson wrote that the largest leakage of such money is through the import of power plants for the rental projects. Pre-shipment inspection had been compulsory in Bangladesh for three years. Forrest Cookson wrote that there was widespread under-invoicing, particularly from China (virtually all orders) and India (40-45 per cent of orders).

Reverse results of govt policy

Why has hundi increased so much in recent times? The World Bank’s South Asia department’s senior economist Zoe Leiyu Xi and consultant Xiao’ou Zhu on 15 June wrote in a blog of the bank that recently many Asian countries imposed various restrictions on the use of foreign exchange in order to preserve scarce foreign exchange reserves. However, these restrictions

However, these restrictions have backfired, and have only served to increase the activities in the informal hundi and hawala markets, thereby further reducing official reserves.

The scope to whiten black money and encouragement to launder money must be stopped. The major tool in this regard is the government’s political will and commitment. That is absent. And so the crisis, for now, will not be resolved.

The two writers cited the example of Bangladesh, saying that when the government imposed restrictions on foreign exchange, the need for hundi increased. Particularly, when restrictions are imposed on opening an LC for import, the smaller importers become dependent on hundi. Even if dollars have to be bought at higher rates, hundi transactions will not decrease. As a result, the dollar rate in the kerb market goes up higher than in the bank.

The two writers also said that in the start of 2022, the informal exchange rate premium in Pakistan was only about 2 per cent more than in the banks. But after the introduction of a temporary import ban of 694 items in May 2022, the premium skyrocketed to 13 per cent by January 2023. Similarly, in Bangladesh, the premium had been hovering around 2 percent before July 2022 when a new regulation was introduced, requiring a 100 per cent advance payment for letter of credits for non-essential items. After that, the premium surged to 12 per cent by August 2022. Analysis shows that a 1 percent deviation between official and informal foreign exchange in Bangladesh shifts 3.6 percent of remittance from the formal to the informal channel.

Earlier, on 31 May the former president of World Bank David Malpass wrote that parallel exchange rates “are expensive, highly distortionary for all market participants, are associated with higher inflation, impede private sector development and foreign direct investment, and lead to lower growth.”

How much hundi?

When asked how much money came in through hundi, finance minister AHM Mustafa Kamal said, a year ago, that 51 per cent of the remittance came in through official channels and 49 per cent through hundi.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) carried out a study on remittance a few years ago. In the report ‘In the Corridor of Remittance: Cost and Use of Remittance in Bangladesh’, ILO said that in the 2012-13 fiscal, expatriates sent USD 14.46 billion dollars in remittance to the country. This was 60 to 70 per cent of the total remittance. That means, another USD 4.3 billion to USD 5.7 billion came in through illegal channels. So a huge volume of remittance is sent through hundi.

The way out

According to the Money Laundering Act, undocumented financial transactions are punishable offence. This can lead up to 12 years imprisonment, a maximum fine of Tk 1 million or confiscation of property. In the case of a company, the penalty can be a maximum fine of Tk 2 million and cancellation of registration. But hundi can never be halted by means or law or police drives.

The two World Bank economists also wrote that currency devaluation or financial incentives are not enough to bring remittance to official channels. On the contrary, weaker local currencies or fiscal incentives in the short run might make the official rates more attractive to migrant workers overseas. However, as long as authorities cannot make the foreign exchange available to the common people at the official rate they set, they will purchase foreign exchange via the informal market at an even more expensive exchange rate.

Actually the problem is quite complex, but no unsolvable. The entire financial sector must be made transparent and accountable. But first the channels of illegal earnings must be blocked. The scope to whiten black money and encouragement to launder money must be stopped. The major tool in this regard is the government’s political will and commitment. That is absent. And so the crisis, for now, will not be resolved.