How cash incentives from taxpayers’ pockets benefit Western RMG buyers

Western brands and buyers are reaping the benefits of Bangladesh’s cash incentives and tax breaks for garment exporters who incorporate these subsidies in their apparel pricing. This practice, however, leaves workers without their fair share despite rising living costs since the minimum wage was set at Tk8,000 per month five years ago.

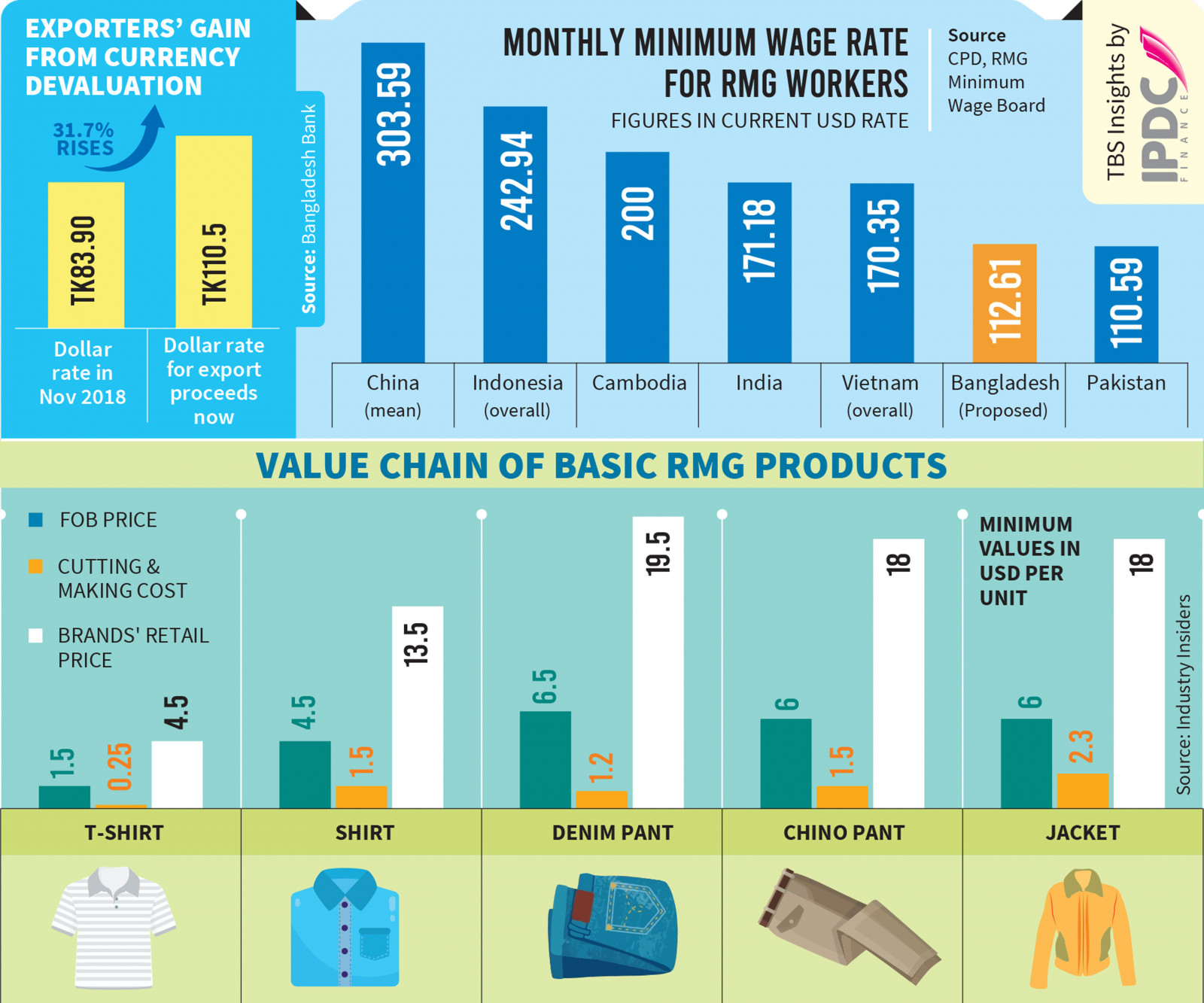

Industry insiders point to the stagnant pricing of basic tee shirts as a prime example of this phenomenon. A decade ago, a basic tee shirt typically sold for around $1.50. Today, that same tee shirt is often sold for the same price or even less due to intense competition among suppliers. Meanwhile, Western retailers often sell these tee shirts for $4.50 each, a significant profit margin.

Likewise, Bangladesh sells a shirt for $4.5 and a pair of denim pants for $6.5 but retailers in the USA and Europe are selling them for $13.5 and $19.5, respectively. This translates to a substantial threefold profit margin for these retailers.

Despite exporters’ claims of a 40% increase in production costs over the past five years, Western buyers resist raising the price of tee shirts made in Bangladesh by even a few cents.

BGMEA President Faruque Hassan said they have been advocating for an increase in the cutting-and-making charge of apparel, but their efforts have been futile.

Cash incentives, tax benefits to RMG

Currently, garment exporters receive a 5% cash incentive when exporting apparel items made from locally procured raw materials such as yarn and fabrics. An additional 4% cash incentive is granted for shipments to non-traditional markets encompassing all export destinations except for the European Union, Canada, and the United States. Furthermore, garment exports benefit from an additional 1% cash incentive in all countries.

According to an OECD and United Nations report “Production Transformation Policy Review of Bangladesh: Investing in the Future of a Trading Nation” released in September, for the fiscal year 2022-23, the total estimated cost of export cash incentives in Bangladesh amounted to Tk7,550 crore ($700 million). This figure represents approximately 10% of the country’s total subsidy expenditure in that year’s budget.

The report says these incentives mostly benefit the RMG sector, as, according to the latest official data from the Government of Bangladesh, 65% of these cash incentives or nearly Tk5,000 crore benefitted the garments and textiles industry.

However, cash incentives are not the sole advantage for garment exporters. They also enjoy a multitude of tax and duty benefits.

According to an estimate by the National Board of Revenue (NBR), the total value of tax subsidies, including rebates, discounts, exemptions, and reduced rates, was estimated to reach Tk1.78 lakh crore in the fiscal year 2022-23. A significant portion of this financial relief benefits the garment exporters.

Wages in Bangladesh and other countries

Currently, the minimum wage for a garment worker in Bangladesh stands at Tk8,000, which is less than $73 based on the current exchange rate of Tk110 for a US dollar. When this wage was established in 2018, Tk 8,000 was equivalent to $94.

In stark contrast, the monthly minimum wage for RMG workers in China exceeds $300, while it’s $200 in Cambodia, $171 in India, $170 in Vietnam, and $110 in Pakistan. Even in Myanmar, the minimum wage is above $100 per month.

Who is pocketing the taxpayers’ money?

These incentives directly benefit Western buyers and their consumers. Exporters have pointed out that American and European brands and buyers offer prices after calculating the incentives the Bangladesh government gives to the exporters.

Iqbal Hossain, who operates a buying house for exporting apparel products to various countries, said, “All businesses do this. It is a common practice.”

However, the actual beneficiaries of these incentives, the producers, employ another tactic by inflating their prices to maximise their gains. For instance, if the true export price of a shirt is $3, some exporters may declare it as $4 to obtain a larger share of the incentive funds. To take advantage of this, they initially export their products at inflated prices to intermediary destinations like Dubai, Hong Kong, Singapore, or other countries first and then re-exporting to their actual intended markets, industry insiders tell TBH.

Owners blame workers’ low productivity

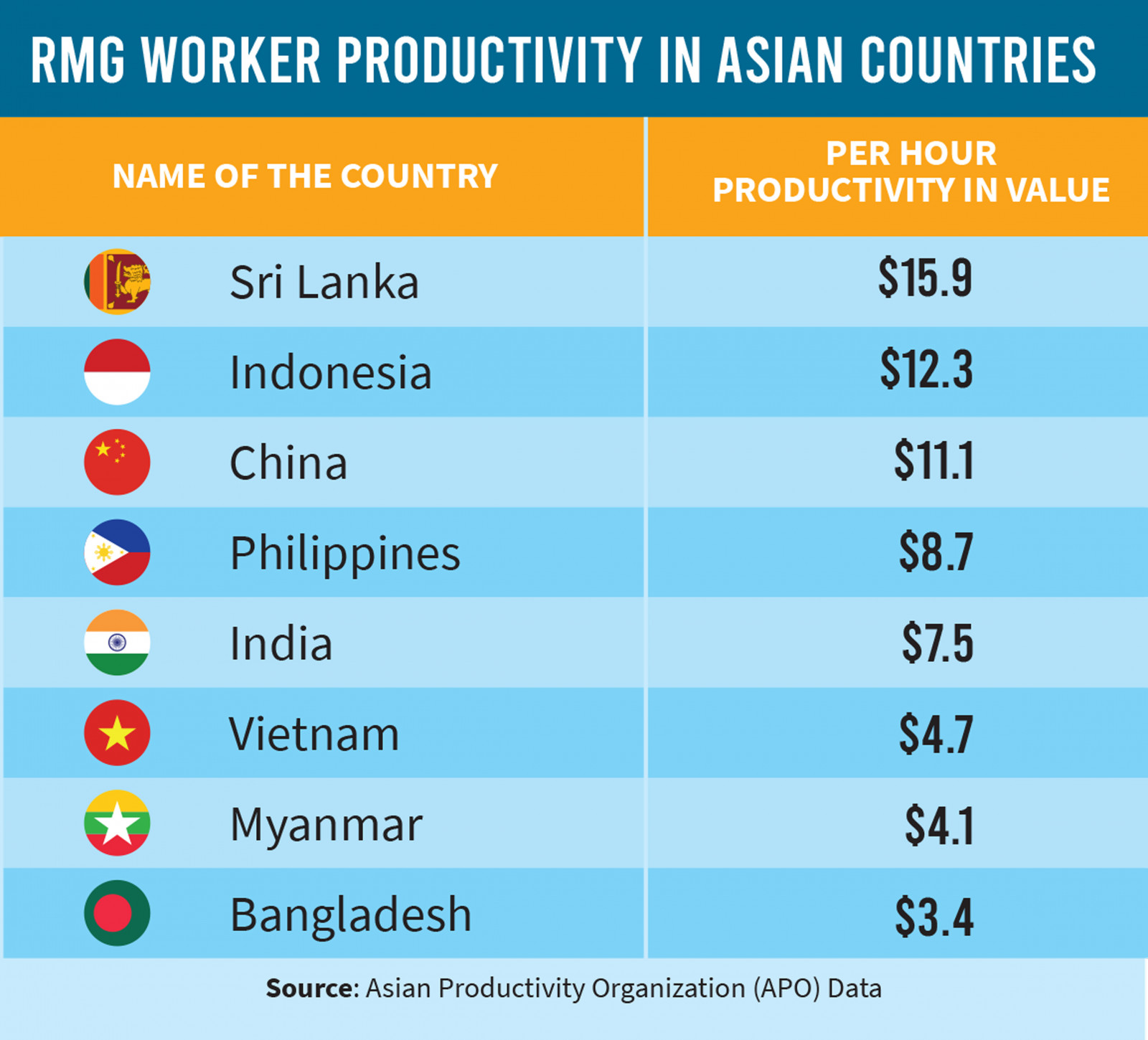

According to data provided by the Asian Productivity Organisation – an intergovernmental organisation committed to improving productivity in the Asia-Pacific region, the hourly productivity of a Bangladeshi garment worker in terms of value stands at $3.4, which is comparatively higher in competing countries: $4.1 in Myanmar, $4.7 in Vietnam, $7.5 in India, $8.7 in the Philippines, over $11 in China, and nearly $16 in Sri Lanka.

Also, the OECD report on Bangladesh underscores that Bangladesh’s labour productivity remains significantly lower when compared to other nations. In 2019, Bangladesh’s labour productivity was merely 9% of that of the USA, while it was 12% and 14% for India and Vietnam, respectively.

Faruque Hassan, president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), emphasised the need to enhance workers’ productivity, reduce waste, and improve resource efficiency within Bangladesh’s apparel industry.

He pointed out, “Although the cost of manufacturing continues to rise annually, we are still falling short of the global benchmark in productivity. Therefore, we must strike a balance in the short term while simultaneously focusing on long-term priorities, such as innovation, technological advancements, and knowledge-based transformation.”

Faruque Hassan underscored that boosting productivity benefits both factories and workers, creating a win-win scenario.

He also highlights the unique challenges faced by Bangladesh, stating that it would be unjust to compare the country to competitors who possess their own raw materials like raw cotton and chemicals, while Bangladesh competes without these inherent advantages.

A BGMEA estimate reveals that the cost of production has surged by over 40% in the past five years.

Mohammad Hatem, executive president of the Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA), said Bangladesh is unique in employing a substantial group of helpers to assist operators, even though production efficiency remains low.

He said after implementing the new wage structure, many factories may discontinue hiring helpers. Piece-rate workers, who are paid based on output, tend to exhibit higher efficiency than those under a fixed wage structure.

Hatem urged a delay of at least three months in implementing the new wage structure to account for the fact that orders are typically received three to six months in advance of production.

Way out of low-wage culture

According to international organisations and local experts, the solution to breaking free from the low-wage culture in the country lies in diversification and innovation.

The OECD report highlights that Bangladesh finds itself ensnared in a cycle of low wages and low productivity, primarily perpetuated by sectors with limited future employment prospects and a failure to create meaningful formal job opportunities.

“The relative less importance of labour shift to more dynamic sectors – activities in which productivity grows faster than the average — contributes to explain the persistence of the productivity gap with respect to the frontier,” says the report.

For example, the report says that Vietnam has seen productivity rise because of the dynamic sectors such as electronics, footwear and semiconductors.

Private sector invests little in innovation

While Bangladesh has made significant strides in establishing itself as a reliable hub for garment manufacturing worldwide, it has yet to transition into an innovation-driven economy.

The nation boasts home-grown firms and a highly influential domestic entrepreneurial class. However, business operations in Bangladesh predominantly fall into two overarching categories: 1) marketing basic and essential products within the protected domestic market, or 2) exporting cost-effective but labour-intensive products that capitalise on the country’s comparative advantage in low labour costs.

These prevailing business strategies are sustained by a targeted policy framework that promotes domestic production through regulations and controls.

In Bangladesh, only 1.2% of firms invest in research and development (R&D) — less than half the rate observed in Indian firms and only 2.6% of Bangladeshi firms employ technologies licensed from foreign counterparts, in stark contrast to Vietnam’s 10.8% and Türkiye’s 14.4%, says the OECD report.

“This is the result not only of the current incentive schemes, which actually lack targeted conditionalities to support innovation and learning but also the prevailing approach of international partners, who still see in Bangladesh a business deal and not an innovation partner,” says the report, adding that the country also suffers from overall gaps in technical and managerial skills for innovation.