Wait for Rohingya repatriation gets even longer

With the escalation of conflict in Myanmar, the possibility of Rohingya repatriation materialising anytime soon has become remote, heaping the challenges for the Bangladesh government in managing the displaced people in the face of shrinking humanitarian aid for them.

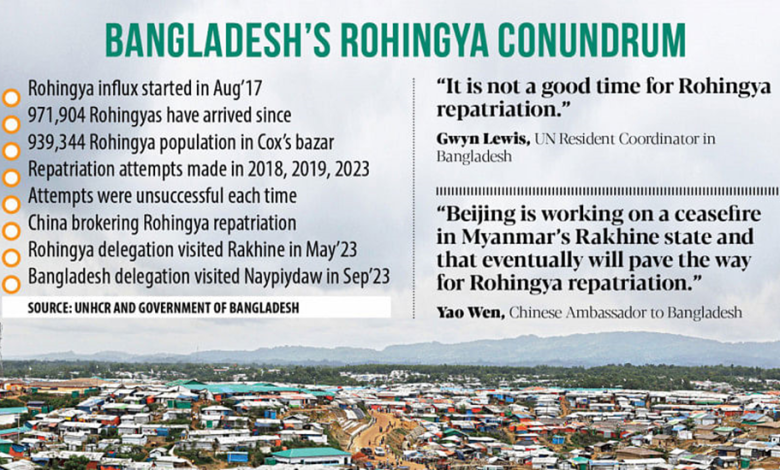

Since the biggest influx of Rohingyas from Myanmar’s Rakhine State in August 2017, there have been three attempts to repatriate Rohingyas: once in 2018, once in 2019 and most recently in 2023.

All three attempts failed as the Rohingyas maintained that there was no guarantee of their safety and citizenship if they went back.

In May last year, a group of Rohingyas visited the Rakhine State for the first time after they fled the land to escape a military clampdown to see the ground reality. Myanmar officials spoke to the Rohingyas in person and verified their identities in the cases that had problems.

Then in July last year, Deng Xijun, the Chinese Special Envoy for Asian Affairs, visited Myanmar and discussed ways to repatriate the Rohingyas from Bangladesh.

Deng brokered an arrangement under which the Rohingyas would be allowed to live in their original villages and not in any camp. This was communicated to Bangladesh in August last year.

For further talks, a delegation from Bangladesh went to the Myanmar capital Naypyidaw the following month.

Under a pilot programme, about 12,000 Rohingyas were supposed to be repatriated in 2023, according to foreign ministry officials.

However, the plan was dashed, first by Cyclone Hamoon and later by the eruption of conflict between Myanmar’s armed opposition groups and the ruling military that began in February 2021. Both the events took place within days of one another.

The Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army and the Arakan Army (AA) from Myanmar’s Shan State joined forces and began a sweeping offensive in late October last year under Operation 1027.

The offensive has seen hundreds of military posts captured; more than 40 towns taken; important trade routes with China, India and Bangladesh affected; and massive supplies of weapons and ammunition brought under the control of the resistance, according to international media reports.

In Rakhine State, the AA has seized more than 160 junta bases, outposts and battalion headquarters across northern Rakhine and in Chin State’s Paletwa, a key western town near the border with India and Bangladesh.

In short, the AA has taken control of much of the Rakhine State, making the possibility of Rohingya repatriation unlikely for now.

“It is not a good time for Rohingya repatriation,” Gwyn Lewis, UN resident coordinator in Bangladesh, told reporters after her meeting yesterday with Foreign Minister Hasan Mahmud.

Asked if the UN asked Bangladesh to accept Rohingyas as many of them are getting displaced in the Rakhine State, Lewis answered in the negative.

“There is no movement of Rohingyas across the Bangladesh-Myanmar border because of the current tense situation. So, there is no request,” she said.

Foreign Minister Hasan Mahmud also acknowledged that the situation in Myanmar is not “very favourable” for Rohingya repatriation.

“In fact, there was always some sort of problem in Myanmar, and we hope that the tension there will dissipate soon. We can then start the repatriation,” he told reporters after his meeting yesterday with Chinese Ambassador Yao Wen.

Beijing is working on a ceasefire in Myanmar’s Rakhine State and that will eventually pave the way for Rohingya repatriation, Yao told reporters.

So far, China has mediated three ceasefire agreements between the military junta and ethnic armed groups in Myanmar during the ongoing conflict in different parts of the country, he said.

Yao urged all to remain “confident” of the joint collaboration of Bangladesh, Myanmar and China to repatriate Rohingyas from Cox’s Bazaar.

Safety and security of the Rohingyas are of paramount importance for their repatriation, said foreign ministry officials on the condition of anonymity to speak candidly on the issue.

“I think it is high time for Bangladesh to expand its policies beyond the state-centric conventional diplomacy when it comes to Myanmar,” said Shahab Enam Khan, a professor at Jahangirnagar University’s International Relations department.

It is imperative to incorporate the growing popularity and influence of non-state actors such as the AA into the decision-making process.

Chinese mediation remains the foremost practical initiative, but the Burmese military has failed to comply with the efforts pursued by its key ally, he said.

It is also a time to explore the feasibility of engaging the Burmese government in exile — the National Unity Government (NUG) — in the repatriation efforts.

“I believe the US and the allies would welcome NUG’s engagement in the repatriation process. Hence, a delicate balance has to be made between these two power centres, which would require greater political and deeper strategic planning,” Khan added.